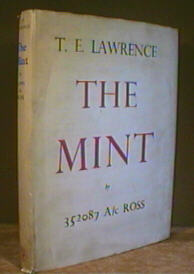

T.E.

LAWRENCE |

NOTE BY A. W. LAWRENCE IN 1922 T. E. Lawrence enlisted

in the ranks of the R.A.F. under the name of John Hume

Ross. From the Depot at Uxbridge he wrote to Edward

Garnett on September 7th of that year: "I find

myself longing for an empty room, or a solitary bed, or

even a moment alone in the open air. However there is

grand stuff here, and if I could write it . . " In a

later letter to Garnett he says that he has been making

notes, "scribbled at night, between last post and

lights out, in bed". They will make, he thinks,

"an iron, rectangular, abhorrent book, one which no

man would willingly read". In January I923 he was

discharged from the R.A.F. upon the discovery of his

identity, but he was allowed to re-enter it two and a

half years later, this time using the name of Shaw, under

which he had meanwhile served in the Tank Corps. On

reenlistment he resumed the taking of notes. In August

1927, writing from Karachi, he tells Garnett that he has

cut up and arranged these notes in sections and is

copying them seriatim into a notebook `as a Christmas

(which Christmas?) gift for you'. In manuscript, or in

typescripts made from it, The Mint was read by a small

number of people, including Bernard Shaw and E. M.

Forster. On August 6th, 1928, answering a letter from

Forster, he wrote the longest account of the genesis of

the book; it should be compared with that on p. I65.

`Every night in Uxbridge I used to sit in bed, with my

knees drawn up under the blankets, and write on a pad the

things of the day. I tried to put it all down, thinking

that memory & time would sort them out, and enable me

to select significant from insignificant. Time passed,

five years and more (long enough, surely, for memory to

settle down?) and at Karachi I took up the notes to make

a book of them . . . and instead of selecting, I fitted

into the book, somewhere & somehow, every single

sentence I had written at Uxbridge. `I wrote it tightly,

because our clothes are so tight, and our lives so tight

in the service. There is no freedom of conduct at all.

Wasn't I right? G.B.S. calls it too dry, I believe. I put

in little sentences of landscape (the Park, the Grass,

the Moon) to relieve the shadow of servitude, sometimes.

For service fellows there are no men on earth, except

other service fellows . . . but we do see trees and

star-light and animals, sometimes. I wanted to bring out

the apartness of us. `You wanted me to put down the way I

left the R.A.F., and something about the Tanks. Only I

still feel miserable at the time I missed because I was

thrown out that first time. I had meant to go on to a

Squadron, & write the real Air Force, and make it a

book - a book, I mean. It is the biggest subject I have

ever seen, and I thought I could get it, as I felt it so

keenly. But they broke all that in me, and I have been

damaged ever since. I could never again recover the

rhythm that I had learned at Uxbridge, resisting Stiffy .

. . and so it would not be true to reality if I tried to

vamp up some yarn of it all now. The notes go to the last

day of Uxbridge, and there stop abruptly. `The Cranwell

part is, of course, not a part, but scraps. I had no

notes for it . . . any more than I am ever likely to have

notes of any more of my R.A.F. life. I'm it, now, and the

note season is over. The Cadet College part was vamped

up, really, as you say, to take off the bitterness, if

bitterness it is, of the Depot pages. The Air Force is

not a man-crushing humiliating slavery, all its days.

There is sun & decent treatment, and a very real

measure of happiness, to those who do not look forward or

back. I wanted to say this, not as propaganda, out of

fairness, the phrase which pricked up your literary ears,

but out of truthfulness. I set out to give a picture of

the R.A.F., and my picture might be impressive and clever

if I showed only the shadow of it . . . but I was not

making a work of art, but a portrait. If it does

surprisingly happen to be literature (I do not believe

you there: you are partially kind) that will be because

of its sincerity, and the Cadet College parts are as

sincere as the rest, and an integral part of the R.A.F.

`Of course I know and deplore the scrappiness of the last

chapters : that is the drawback of memory, of a memory

which knew it was queerly happy then, but shrank from

digging too deep into the happiness, for fear of

puncturing it. Our contentments are so brittle, in the

ranks. If I had thought too hard about Cranwell, perhaps

I'd have found misery there too. Yet I assure you that it

seems all sunny, in the back view. 'Of Cadet College I

had notes. Out of letters on Queen Alexandra's Funeral

(Garnett praises that. Shaw says it's the meanness of a

guttersnipe laughing at old age. I was so sorry and sad

at the poor old queen), for the hours on guard, for the

parade in the early morning. The Dance, the Hangar, Work

and the rest were written at Karachi. They are

reproductions of scenes which I saw, or things which I

felt & did . . . but two years old, all of them. In

other words, they are technically on a par with the

manner of The Seven Pillars: whereas the Notes were

photographs, taken day by day, and reproduced complete,

though not at all unchanged. There was not a line of the

Uxbridge notes left out; but also not a line unchanged.

`I wrote The Mint at the rate of about four chapters a

week, copying each chapter four or five times, to get it

into final shape. Had I gone on copying, I should only

have been restoring already crossed out variants. My mind

seems to congest, after reworking the stuff several

times. `To insist that they are notes is not

side-tracking. The Depot section was meant to be a quite

short introduction to the longer section dealing with the

R.A.F. in being, in flying work. Events killed the longer

book: so you have the introduction, set out at greater

length.' In a subsequent letter to Forster he explained

that he felt unable to publish the book because of `the

horror the fellows with me in the force would feel at my

giving them away, at their "off" moments, with

both hands . . . So The Mint shall not be circulated

before 1950.' But to Garnett he wrote: `I took liberties

with names, and reduced the named characters of the squad

from 50 odd to about 15.' (Since the extent of the

`liberties' is unknown, new names have been substituted

in this edition in all passages which might have caused

embarrassment or distress.) The author portrays himself

at a time when he was nervously exhausted, following the

intense and almost continuous strain involved by the war,

by the struggle for post-war settlement, by the writing

of Seven Pillars and by writing the whole again after the

theft of the original manuscript. Otherwise the

starvation described in Chapter I would have been

avoidable; as Colonel S. F. Newcombe points out, during

some months before enlistment he received sufficient

money to have enabled him to live comfortably, and in the

last few weeks he caused some annoyance by constantly

refusing invitations to meals and by failing to visit

households at which he would have always been welcome.

Presumably the years of over-exertion had resulted, when

the need for activity ceased, in a condition of mind

which allowed only negative decisions to be taken without

intolerable effort. Life in the ranks, where a decision

would never be required, therefore seemed the right

solution, though to a man in such a state the rigours

were bound to be magnified. The account of them, it need

scarcely be said, was not written as propaganda for

alleviating |

CONTENTS NOTE BY A. W. LAWRENCE PART ONE. THE RAW MATERIAL 1 RECRUITING OFFICE PART TWO. IN THE MILL 1 DISCIPLINES PART THREE. SERVICE AN EXPLANATION |

II . FATIGUES FATIGUES, fatigues, fatigues. They break our spirits upon this drudgery. One of . us ninety recruits (to so many are we grown) already wishes aloud he had not joined the R.A.F. In under a week we have clicked three or four fire-pickets, (`Swinging it on the . rookies, they are, the old sweats' grumbled Tug. `Old soldier, old ' quoted Madden with a laugh. `Ah,' flung back Tug malevolently, `young soldier, fly . hat's me') dust-cart we get, and refuse-collection, scrubbing the shit-houses, the butcher's shop, the Q.M. Stores, Barrack Stores, sweeping and dusting the Cinema. Then there's message running at H.Q., the main point of which is to bring back for the clerk's elevenses their Chelsea buns while warm. China got into disgrace there. `I wasn't going to ******* about for those toffy-nosed ******* , so I got back after ****** twelve, and they shoved me on the fizzer!' He received two extra fatigues, as punishment: - which was getting off scot-free, for we are all, innocent and guilty, on extra fatigues, what with stoking the boiler-house or in the cook-house, or at the officers' mess, or hut cleaning or polishing the fire-station, or washing down the pigsties, or feeding the incinerator. At dawn we leap from bed, rush to wet our hands and faces, fall in for P.T.: fall out and fall in for breakfast, put on puttees and overalls, sweep the hut (under the eye of our corporal, who has us all by name, and misses nothing of what we fail to do), tidy our beds again, and fall in for fatigues. After that the hut does not see us, except for a hurried moment each side of dinner, till tea-time: and after tea is fire-picket, save for those who work an evening shift till nine at officers' mess, or dining hall, or civilian hut. These two last are scullion jobs: - and not in neat sculleries with sinks and racks and hot taps. We dip into a tub of cold water, through its crusted grease, four or five hundred tea-stained mugs and a thousand plates: which afterwards we smooth over with a ball of grease-stiff rag. A stomach-turning smell and feel of muck it is, for hour upon hour: and a chill of water which shrivels our fingers. Then a clattered piling of wet dishes on the table, to drip dry. Nor may you ever call yourself your own, or a job yours. The camp pullulates with recruits, and every employed man's our master, who will get from us what privy convenience he can. Many exercise a spite upon the recruits so that out of fear we may be more accommodating. The Sergeant Major set an example of misuse, when he led the last fatigue man in the rank to his wife's house, and had him black the grate and mind the children, while she shopped. `Gave me a slab of jam-tart, she did,' boasted Garner, lightly forgiving the crying infant because of the belly-full he'd won. We are always hungry. The six-weeks men we meet on fatigues shock our moral sense by their easy-going. `You're silly , you rookies, to sweat yourselves' they say. Is it our new keenness, or a relic of civility in us? For by the R.A.F. we shall be paid all the twenty-four hours a day, at three halfpence an hour; paid to work, paid to eat, paid to sleep: always those halfpence are adding up. Impossible, therefore, to dignify a job by doing it well. It must take as much time as it can for afterwards there is not a fireside waiting, but another job. The gods allow us in our hut just long enough to clean it, and our brass and leather and cloth - and they make the hut bare and regimental, so that we do not wish to linger in it. Our days pass half choked in dusty offices, or menially in squalid kitchens, to and from which we hurry at a quick-step in fours through the verdant beauty of the park and its river valley: the stamp of our armoured feet fighting down the thrushes' twitter and the grave calling of rooks in the high elms. |

|